The End of Poetry

By Ada Limón (from The New Yorker)

Enough of osseous and chickadee and sunflower

and snowshoes, maple and seeds, samara and shoot,

enough chiaroscuro, enough of thus and prophecy

and the stoic farmer and faith and our father and tis

of thee, enough of bosom and bud, skin and god

not forgetting and star bodies and frozen birds,

enough of the will to go on and not go on or how

a certain light does a certain thing, enough

of the kneeling and the rising and the looking

inward and the looking up, enough of the gun,

the drama, and the acquaintance’s suicide, the long-lost

letter on the dresser, enough of the longing and

the ego and the obliteration of ego, enough

of the mother and the child and the father and the child

and enough of the pointing to the world, weary

and desperate, enough of the brutal and the border,

enough of can you see me, can you hear me, enough

I am human, enough I am alone and I am desperate,

enough of the animal saving me, enough of the high

water, enough sorrow, enough of the air and its ease,

I am asking you to touch me.

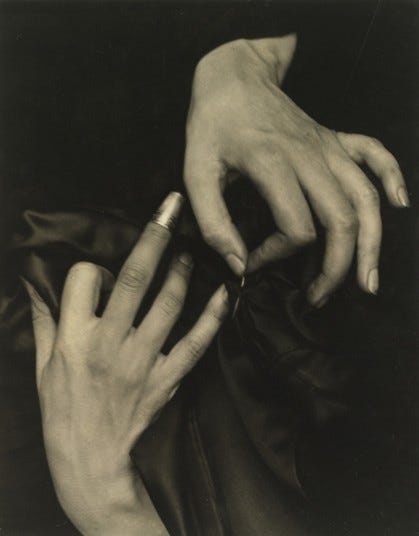

I love this Ada Limón poem for its paradox: it points to what poetry always does (to the point of cliché) and what it can’t do—touch, sensation, the limitations of language that every writer wrestles with—and in doing so, it does exactly what it said is impossible—reach out from the page and take your hand and just hold it for a while.

The act of writing is nothing except approaching the experience written about; just as, hopefully, the act of reading the written text is a comparable act of approach.

- John Berger, from“The Storyteller”

I haven’t been writing. Well, that’s not true, I have, but I’m doing revision, the kind of writing that’s never really visible in the final piece, the kind of writing that entails a lot of not-writing as you step back and look at the piece like a painter to figure it out, the kind of writing that gets lost in nit-picky details that make whole afternoons disappear entirely. In a culture so focused on cycles of productivity, I need to remind myself that just looking is also an action, not passivity or a lack of value, and that it will lead to (“produce”) something in due time. Looking over my manuscript, I find scraps of things I’ve witnessed going about my life when I wasn’t writing at all. Besides, I’m writing now, to you. I’m writing about writing.

I’m bored by the always-lazy logic in those “what’s-the-point-of-poetry” hot takes that seem to pop up every year or so, and I think Limón’s title pokes fun at them. Rather than engaging in that tiresome discourse, let’s just assume that if you’re reading this you see art having a redemptive purpose that persists in our current corporate hegemonic hellscape. So with today’s episode, I’m going to explore how art and writing save us, offers us another option, an escape, a voice, a hand to hold.

My mentor and professor, John Skoyles, often shared this video of the artist Paul Resika’s creative process with his classes because, I think, he knew we’d each find a piece of ourselves reflected here, whether that’s in Resika’s persistence, the importance of looking, orthe exploratory nature of embarking without a plan. Skoyles is friends with Resika, and apparently Resika told him he finally figured out what was wrong with it a year later. It hits close to home with my own not-writing writing.

While there are clear parallels in the creative processes of painting and poetry, I’ve recently accumulated a small collection of quotes from writers trying to describe how processes vary by genre or medium, and drawing those differences can be just and instructive as finding parallels. Here are some favorites:

In nonfiction the notes give you the piece. Writing nonfiction is more like sculpture, a matter of shaping the research into the finished thing. Novels are like paintings, specifically watercolors. Every stroke you put down you have to go with. Of course you can rewrite, but the original strokes are still there in the texture of the thing. - Joan Didion from a 2006 interview in The Paris Review

If prose is a house, poetry is a man on fire running quite fast through it. - Anne Carson in a 2106 interview with The Guardian

Writing isn’t hard the way physical labor, or recovery from surgery, is hard; it’s hard the way math or physics is hard, the way chess is hard. What’s hard about art is getting any good—and then getting better. What’s hard is solving problems with infinite solutions and your finite brain. - from Elisa Gabbert’s essay, “Why Write,”also in the Paris Review (and beginning with a different Didion quote )

I recently discovered this old interview of Joni Mitchell in which she observes that the music industry is “no longer looking for talent, they want people with a certain look and a willingness to cooperate,” and responds with this incredible point about the point of art:

I believe a total unwillingness to cooperate is what is necessary to be an artist -- not for perverse reasons, but to protect your vision. The considerations of a corporation, especially now, have nothing to do with art or music. That’s why I spend my time now painting.

I was lucky enough to be in a writing workshop last winter with Nickole Brown where she brought in part of this essay, now recently published in Orion. I’d be enamored by the rhythm and strength and heart in the voice of this essay even if I didn’t have the memory of Nickole’s voice nearly turning the words to song, even if I didn’t know what an absolutely wonderful person she is. Take my word for it. Go read it.

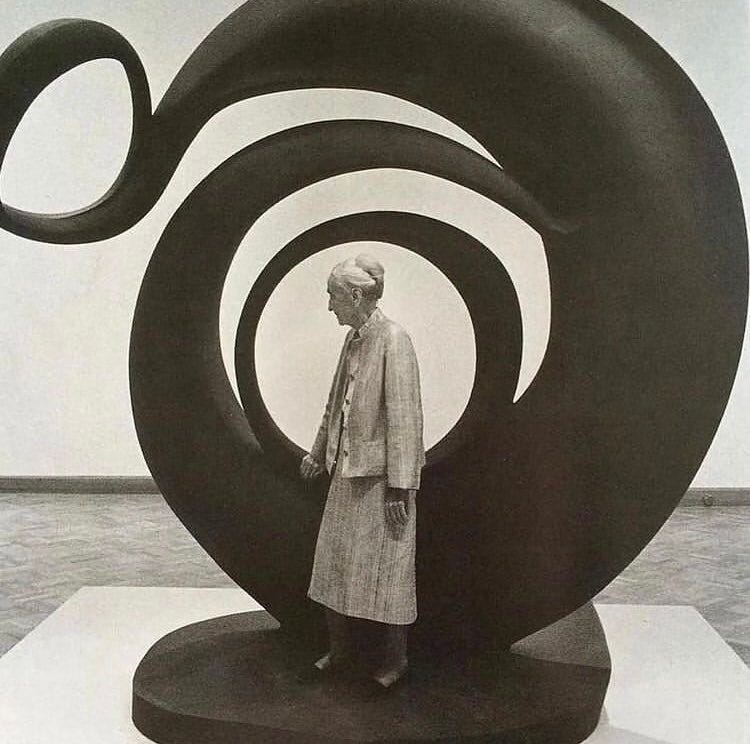

In this essay, Nickole looks at two memories, one distant and nearly forgotten and one more recent, and thinks about the act of remembering itself. They are memories of looking, moments that could have passed by and been forgotten but for the work of witnessing. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that Nickole’s deliberate act of looking mirrors Paul Resika saying most of the time he’s painting he’s just looking. Looking is important, and art and writing have the capacity to preserve what we witness.

Because above me now, I see my memories—all our memories—as an aggregation tossed aside by impossibly wrong winds. I see them as a kettle of winged things circling, circling, not sure where to land, but hungry and smelling yet another of their own kind dismantling in a tree.

Because survival has to do with remembering what you most do not want to face. It has to do with not turning away, in believing your own testimony, in writing it down. Years ago, the act of writing wasn’t just about casting light on the dank recesses of my childhood, but just this—rising up to share words to help others who have passed through the same.

If art—both the process of making it and the experience of it—is about looking, about taking the time to pause and remember and witness, then it is an important and radical way of interacting with the world. If late-stage capitalism feels like we live in a cult of productivity, where we’re objectified and valued by what we produce, then not making, pausing to be, to simply exist for a moment is what can save us. And art and writing are the best tools we have for preserving that experience of looking. Art can reach out a hand, and you, viewer or reader, can hold it and be with it and share a moment of humanity.

Nocturne

by Kwame Opoku-Duku

When at a loss for words—during, perhaps,

a time of want or desire, when one’s body

is overwhelmed by light, as if by the effect

of Ketamine or MDMA, when overwhelmed

by the weight of the moment, the silence,

the look of disappointment in a lover’s eyes—

what do we call the moment, then, when

the words are finally summoned, like a

sparkle of fireflies, and by grace, by the

mercy of the night, what was damaged

has been restored? Freire spoke that one reads the world

before they read the word, which suggests that the

first stage of language is in the experiencing of a thing

to the point of knowing; in this knowing,

then—of song sparrows and house sparrows,

of catbirds and European Starlings, of a lover’s wants

and needs, one could say, genuinely, that knowing

to the point of the words conjuring themselves

is, perhaps, the truest form of love.

In Los Angeles, my lover drove me to the airport.

It was mid-summer, and along the highway, the neon sun

poked through a grove of palm trees, its corona

pink with a thick haze of smog. In my youth,

in the hope of producing a kind of love, I attempted

to acquire the words to conjure a new world—of which

I was god—not god as in God, but yes, as in the creator.

After watching the television series WandaVision, I see now

how foolish a person can seem when they want to be loved.

Maybe foolish isn’t the word. Anyway, we stopped

to eat ramen a few miles from the airport, and when

we returned to the car and sat inside, she leaned into me and

whispered the words, Don’t go. I whispered back,

I don’t want to go. And yet I did. I flew back

to LaGuardia on a red-eye flight. What is the

word for the kind of sadness that comes

from having to leave a place where one is loved?

What is the word for a lover who says,

I don’t want to go but goes?